mirror of

https://github.com/trekhleb/javascript-algorithms.git

synced 2025-12-19 08:59:05 +08:00

Chore(math-translation-FR-fr): a pack of translations for the math section (#558)

* chore(factorial): translation fr-FR * feat(math-translation-fr-FR): fast powering * feat(math-translation-fr-FR): fibonacci numbers * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): bits * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): complex number * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): euclidean algorithm * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): fibonacci number * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): fourier transform * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): fourier transform WIP * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): fourier transform done * chore(math-translation-fr-FR): fourier transform in menu

This commit is contained in:

49

src/algorithms/math/euclidean-algorithm/README.fr-FR.md

Normal file

49

src/algorithms/math/euclidean-algorithm/README.fr-FR.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,49 @@

|

||||

# Algorithme d'Euclide

|

||||

|

||||

_Read this in other languages:_

|

||||

[english](README.md).

|

||||

|

||||

En mathématiques, l'algorithme d'Euclide est un algorithme qui calcule le plus grand commun diviseur (PGCD) de deux entiers, c'est-à-dire le plus grand entier qui divise les deux entiers, en laissant un reste nul. L'algorithme ne connaît pas la factorisation de ces deux nombres.

|

||||

|

||||

Le PGCD de deux entiers relatifs est égal au PGCD de leurs valeurs absolues : de ce fait, on se restreint dans cette section aux entiers positifs. L'algorithme part du constat suivant : le PGCD de deux nombres n'est pas changé si on remplace le plus grand d'entre eux par leur différence. Autrement dit, `pgcd(a, b) = pgcd(b, a - b)`. Par exemple, le PGCD de `252` et `105` vaut `21` (en effet, `252 = 21 × 12` and `105 = 21 × 5`), mais c'est aussi le PGCD de `252 - 105 = 147` et `105`. Ainsi, comme le remplacement de ces nombres diminue strictement le plus grand d'entre eux, on peut continuer le processus, jusqu'à obtenir deux nombres égaux.

|

||||

|

||||

En inversant les étapes, le PGCD peut être exprimé comme une somme de

|

||||

les deux nombres originaux, chacun étant multiplié

|

||||

par un entier positif ou négatif, par exemple `21 = 5 × 105 + (-2) × 252`.

|

||||

Le fait que le PGCD puisse toujours être exprimé de cette manière est

|

||||

connue sous le nom de Théorème de Bachet-Bézout.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

La Méthode d'Euclide pour trouver le plus grand diviseur commun (PGCD)

|

||||

de deux longueurs de départ`BA` et `DC`, toutes deux définies comme étant

|

||||

multiples d'une longueur commune. La longueur `DC` étant

|

||||

plus courte, elle est utilisée pour « mesurer » `BA`, mais une seule fois car

|

||||

le reste `EA` est inférieur à `DC`. `EA` mesure maintenant (deux fois)

|

||||

la longueur la plus courte `DC`, le reste `FC` étant plus court que `EA`.

|

||||

Alors `FC` mesure (trois fois) la longueur `EA`. Parce qu'il y a

|

||||

pas de reste, le processus se termine par `FC` étant le « PGCD ».

|

||||

À droite, l'exemple de Nicomaque de Gérase avec les nombres `49` et `21`

|

||||

ayan un PGCD de `7` (dérivé de Heath 1908: 300).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Un de rectangle de dimensions `24 par 60` peux se carreler en carrés de `12 par 12`,

|

||||

puisque `12` est le PGCD ed `24` et `60`. De façon générale,

|

||||

un rectangle de dimension `a par b` peut se carreler en carrés

|

||||

de côté `c`, seulement si `c` est un diviseur commun de `a` et `b`.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Animation basée sur la soustraction via l'algorithme euclidien.

|

||||

Le rectangle initial a les dimensions `a = 1071` et `b = 462`.

|

||||

Des carrés de taille `462 × 462` y sont placés en laissant un

|

||||

rectangle de `462 × 147`. Ce rectangle est carrelé avec des

|

||||

carrés de `147 × 147` jusqu'à ce qu'un rectangle de `21 × 147` soit laissé,

|

||||

qui à son tour estcarrelé avec des carrés `21 × 21`,

|

||||

ne laissant aucune zone non couverte.

|

||||

La plus petite taille carrée, `21`, est le PGCD de `1071` et `462`.

|

||||

|

||||

## References

|

||||

|

||||

[Wikipedia](https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Algorithme_d%27Euclide)

|

||||

@@ -1,55 +1,58 @@

|

||||

# Euclidean algorithm

|

||||

|

||||

In mathematics, the Euclidean algorithm, or Euclid's algorithm,

|

||||

is an efficient method for computing the greatest common divisor

|

||||

(GCD) of two numbers, the largest number that divides both of

|

||||

_Read this in other languages:_

|

||||

[français](README.fr-FR.md).

|

||||

|

||||

In mathematics, the Euclidean algorithm, or Euclid's algorithm,

|

||||

is an efficient method for computing the greatest common divisor

|

||||

(GCD) of two numbers, the largest number that divides both of

|

||||

them without leaving a remainder.

|

||||

|

||||

The Euclidean algorithm is based on the principle that the

|

||||

greatest common divisor of two numbers does not change if

|

||||

the larger number is replaced by its difference with the

|

||||

smaller number. For example, `21` is the GCD of `252` and

|

||||

`105` (as `252 = 21 × 12` and `105 = 21 × 5`), and the same

|

||||

number `21` is also the GCD of `105` and `252 − 105 = 147`.

|

||||

Since this replacement reduces the larger of the two numbers,

|

||||

repeating this process gives successively smaller pairs of

|

||||

numbers until the two numbers become equal.

|

||||

When that occurs, they are the GCD of the original two numbers.

|

||||

The Euclidean algorithm is based on the principle that the

|

||||

greatest common divisor of two numbers does not change if

|

||||

the larger number is replaced by its difference with the

|

||||

smaller number. For example, `21` is the GCD of `252` and

|

||||

`105` (as `252 = 21 × 12` and `105 = 21 × 5`), and the same

|

||||

number `21` is also the GCD of `105` and `252 − 105 = 147`.

|

||||

Since this replacement reduces the larger of the two numbers,

|

||||

repeating this process gives successively smaller pairs of

|

||||

numbers until the two numbers become equal.

|

||||

When that occurs, they are the GCD of the original two numbers.

|

||||

|

||||

By reversing the steps, the GCD can be expressed as a sum of

|

||||

the two original numbers each multiplied by a positive or

|

||||

negative integer, e.g., `21 = 5 × 105 + (−2) × 252`.

|

||||

The fact that the GCD can always be expressed in this way is

|

||||

By reversing the steps, the GCD can be expressed as a sum of

|

||||

the two original numbers each multiplied by a positive or

|

||||

negative integer, e.g., `21 = 5 × 105 + (−2) × 252`.

|

||||

The fact that the GCD can always be expressed in this way is

|

||||

known as Bézout's identity.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

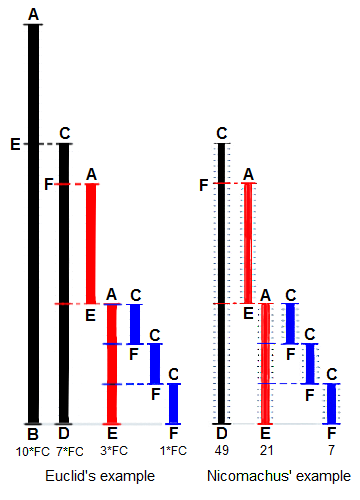

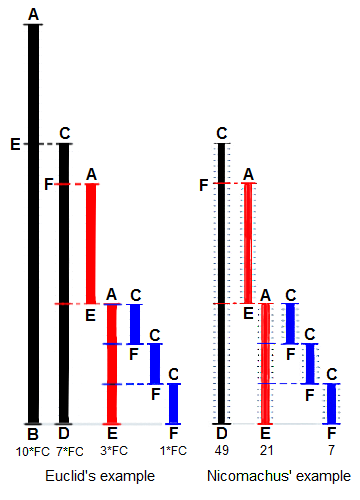

Euclid's method for finding the greatest common divisor (GCD)

|

||||

of two starting lengths `BA` and `DC`, both defined to be

|

||||

multiples of a common "unit" length. The length `DC` being

|

||||

shorter, it is used to "measure" `BA`, but only once because

|

||||

remainder `EA` is less than `DC`. EA now measures (twice)

|

||||

the shorter length `DC`, with remainder `FC` shorter than `EA`.

|

||||

Then `FC` measures (three times) length `EA`. Because there is

|

||||

no remainder, the process ends with `FC` being the `GCD`.

|

||||

On the right Nicomachus' example with numbers `49` and `21`

|

||||

Euclid's method for finding the greatest common divisor (GCD)

|

||||

of two starting lengths `BA` and `DC`, both defined to be

|

||||

multiples of a common "unit" length. The length `DC` being

|

||||

shorter, it is used to "measure" `BA`, but only once because

|

||||

remainder `EA` is less than `DC`. EA now measures (twice)

|

||||

the shorter length `DC`, with remainder `FC` shorter than `EA`.

|

||||

Then `FC` measures (three times) length `EA`. Because there is

|

||||

no remainder, the process ends with `FC` being the `GCD`.

|

||||

On the right Nicomachus' example with numbers `49` and `21`

|

||||

resulting in their GCD of `7` (derived from Heath 1908:300).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

A `24-by-60` rectangle is covered with ten `12-by-12` square

|

||||

tiles, where `12` is the GCD of `24` and `60`. More generally,

|

||||

an `a-by-b` rectangle can be covered with square tiles of

|

||||

A `24-by-60` rectangle is covered with ten `12-by-12` square

|

||||

tiles, where `12` is the GCD of `24` and `60`. More generally,

|

||||

an `a-by-b` rectangle can be covered with square tiles of

|

||||

side-length `c` only if `c` is a common divisor of `a` and `b`.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Subtraction-based animation of the Euclidean algorithm.

|

||||

The initial rectangle has dimensions `a = 1071` and `b = 462`.

|

||||

Squares of size `462×462` are placed within it leaving a

|

||||

`462×147` rectangle. This rectangle is tiled with `147×147`

|

||||

squares until a `21×147` rectangle is left, which in turn is

|

||||

tiled with `21×21` squares, leaving no uncovered area.

|

||||

Subtraction-based animation of the Euclidean algorithm.

|

||||

The initial rectangle has dimensions `a = 1071` and `b = 462`.

|

||||

Squares of size `462×462` are placed within it leaving a

|

||||

`462×147` rectangle. This rectangle is tiled with `147×147`

|

||||

squares until a `21×147` rectangle is left, which in turn is

|

||||

tiled with `21×21` squares, leaving no uncovered area.

|

||||

The smallest square size, `21`, is the GCD of `1071` and `462`.

|

||||

|

||||

## References

|

||||

|

||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user